1969 CHARLESTON STRIKE Victory

March 6, 2023

The Union leads the charge against racial and economic oppression.

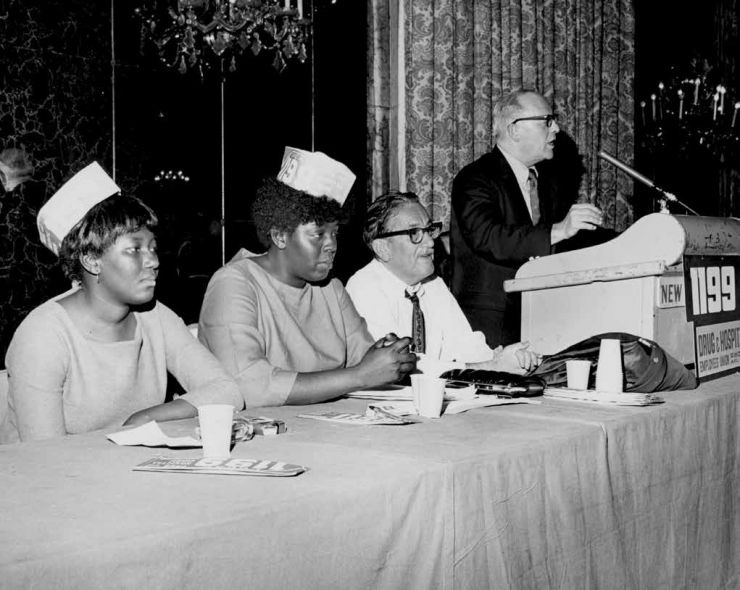

In the spring of 1969, some 450 workers – 90 percent African- American women – struck the Medical College Hospital of the University of South Carolina (MCH) and the smaller Charleston County Hospital after 12 workers at MCH were unjustly fired. One of those fired, an MCH nurse’s aide named Mary Moultrie who had previously worked in New York City as an LPN but whose credentials MCH management refused to accept, led the strikers. Months earlier, Moultrie had been elected president of Local 1199B, the Union’s first out-of state local.

William McCord, the contemptuous president of MCH, was born to American parents in South Africa and his views mirrored those of that apartheid nation. When questioned about union recognition, Business Week reported McCord replied, “I’m not about to turn a $2.5 million complex over to a bunch of people who don’t have a grammar school education.”

His attitude was shared by the overwhelming majority of the state’s power structure. Every formal lever of power and influence was overtly hostile to the organizing effort. The workers were treated like chattel and earned poverty wages. Although about one-third of Charleston residents were Black, there wasn’t a single Black member of the state legislature, and very few Black city officials. Nearly half of Black residents lived below the poverty line.

Many of the workers spoke about the inspiration they drew from Coretta Scott-King’s presence — the honorary chairperson of 1199’s national union.

The city’s power structure and the hospitals saw the organizing campaign as outside intrusion by Northern radicals. To negotiate was out of the question.

The bitter strike lasted 113 days, during which 1,000 people—including 1199 Pres. Leon Davis and SCLC head. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy—were jailed. Violence against the strikers included the bombing of organizer Henry Nicholas’s hotel room. Ultra-conservative racists such as Republicans Sen. Strom Thurmond and Rep. L Mendel Rivers worked behind the scenes against the strike.

A national political campaign helped turn the tide. 1199’s genius publicist Moe Foner contacted media and public officials who focused the nation’s attention on the struggle, noting that the struggle was for the jobs and freedom that were demanded at the 1963 March on Washington. He stressed that Dr. King had given his life fighting for the rights of poor workers.

Soon, members of Congress, some 25 Representatives and 17 Senators, led by Jacob Javits (R-NY) and Walter Mondale (D-MN), urged federal mediation.

SCLC’s Andrew Young, who would later serve as Atlanta’s mayor and the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, played a prominent role in the campaign, organizing a town boycott and building local support. The local Catholic Church was especially supportive.

Civil rights heroes including the Rev. Jesse Jackson and the late John Lewis helped gather political support, which also included members of the Kennedy family.

The Nixon administration remained reluctant to intervene, but a conversation with James Farmer, the founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who was undersecretary of the Department of Health Education and Welfare (HEW) at the time, indicated a path forward.

HEW had initiated an investigation of the Medical College Hospital for violations of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the firing of the 12 workers—$15 million in federal funding was at stake. The hospital settled on June 27.

The settlement did not recognize the Union, but it returned the 12 fired workers, provided a grievance procedure, a wage increase, and a credit union. Other changes had also been set in motion. Black workers finally began to be treated with respect. African-Americans were elected to the state legislature, and over the next decade Black representation in Charleston’s City Council jumped from one to six.