Public Advocate: Jumaane Williams Wins Special Election in New York City

February 27, 2019

By Jeffery C. Mays | The New York Times

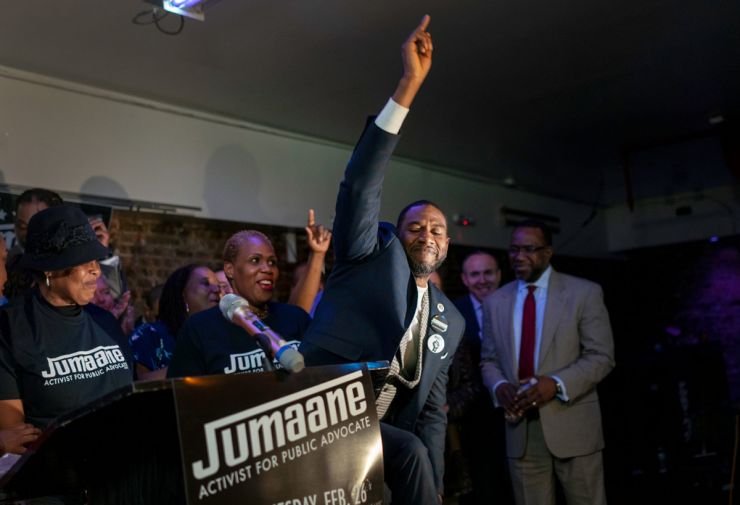

Jumaane Williams, a Brooklyn city councilman, addressing his followers at a victory party on Tuesday. Photo Credit: Todd Heisler | The New York Times

Jumaane D. Williams, a Democratic councilman from Brooklyn, was elected as New York City public advocate Tuesday night, notching a victory over 16 other candidates in a free-for-all race that could give him a platform to seek higher office.

Mr. Williams entered the race as a front-runner after his surprise insurgency campaign for lieutenant governor against the Democratic incumbent, Kathy Hochul, netted him more than 434,000 votes in New York City in a losing effort last year.

He used that momentum to argue that he had the support of voters who saw his history as an activist — including several arrests for civil disobedience — as evidence that he would be an unapologetic antagonist to Mayor Bill de Blasio when needed.

As Mr. Williams took the stage at Cafe Omar in Flatbush to give his acceptance speech, he appeared buoyant, mouthing the words to “Differentology,” a song by the soca artist, Bunji Garlin. He swayed to the beat and mouthed the words to the chorus, “We ready for the road,” before addressing the crowd.

“We cannot wait, we cannot stand still, because the challenges in our city are too great,” Mr. Williams said. “But the opportunity to create change is even greater.”

He pledged to listen to his fellow New Yorkers and then take action on behalf of the city’s most disadvantaged residents, naming people living in public housing and victims of gun violence. He vowed to help “ upend a system of injustice that criminalizes black and brown communities, and to give those who have been caught in the system a second chance. Most of them, a first chance.”

The speech ended on an emotional note, as Mr. Williams, in tears, spoke of being in therapy for the last three years, building up his self-worth.

The public advocate serves as an ombudsman to the city and is first in line to succeed a mayor departing before the end of his term. It is also seen as a potential launching pad to higher office; Mr. de Blasio went from being public advocate to becoming mayor.

“I would call this race an education in New York City civics,” said a Democratic political strategist, Lupe Todd-Medina. “It had money, politics and sex. It’s a case study.”

With Mr. de Blasio openly flirting with a run for the Democratic nomination for president, the public advocate role may be more important than people know, said Jeanne Zaino, a professor of political science at Iona College.

“Anytime you see a mayor eyeing something bigger on the horizon, this is a natural position from which you will get a major candidate,” she said.

Mr. Williams has said he will not run for mayor in 2021. “To the mayor, I’m not running for your job!” he said, laughing. “But together we have to make sure the government is working on behalf of the people.”

With 97 percent of precincts reporting and about 396,000 ballots cast, Mr. Williams had 33 percent of the vote, according to preliminary totals from the Board of Elections.

Eric A. Ulrich, a Republican councilman from Queens, came in second with 19 percent of the vote and the former City Council speaker, Melissa Mark-Viverito, a Democrat, was third with 11 percent.

At times, the contest was a referendum on Mr. de Blasio’s policies, the state of the city’s subways and a failed plan for Amazon to build a campus in Long Island City. And in the campaign’s final days, a previously undisclosed decade-old arrest of Mr. Williams became an issue.

Mr. Williams was forced to acknowledge that he had been arrested a decade ago on harassment and criminal mischief charges, and spent a night in custody after what he called a “verbal disagreement” with his girlfriend at the time. Charges were dropped, and the arrest record itself is sealed.

But the arrest was leaked to the media, and Mr. Williams’s opponents used it to question his fitness for the office.

Mr. Williams said he did nothing wrong, accusing his opponents of resorting to tired racial stereotypes by trying to paint him as an “angry black man” to discredit him with voters. In his victory speech, Mr. Williams thanked “most” of the other candidates.

“I think people were politicizing this issue. His opponents went back 10 years out of desperation,” said Rodneyse Bichotte, a State assemblywoman from Brooklyn and Mr. Williams’s campaign chairwoman.

Indeed, some people who spoke with Mr. Williams as he campaigned on Election Day brought up his other arrests, during protests of issues such as criminal justice reform. And he met a man who served as a juror on his trial for blocking an ambulance during an immigrants rights protest. Mr. Williams was found guilty of disorderly conduct and sentenced to time served.

“I want to leave it to people’s judgment,” Mr. Williams said. “And people’s judgment is telling them that there’s nothing there.”

Candidates also made an issue of the lack of racial and gender diversity among the city’s leadership; in a remarkable display of diversity not normally seen in city elections, 12 of the 17 candidates are women or minorities, including Ms. Mark-Viverito, who was one of the perceived front-runners.

Although Ms. Mark-Viverito enjoyed more name recognition than many of her opponents, the election was the first test of her citywide appeal.

In her concession speech at an East Harlem pub, Ms. Mark-Viverito said her campaign “highlighted the shameful lack of diversity in citywide leadership, where we have three white men in every single position of citywide office,” she said, urging more women to follow her example and seek political office.

Of all the candidates in the race, Ms. Mark-Viverito’s political future seemed the most unclear. She declined to say whether she would run for the same seat again.

“For Mark-Viverito, you have to wonder where she goes from here,” Professor Sherrill said. “Losing has a real cost for her.”

The candidates consisted of multiple City Council members blocked from running for their seats again by term limits and State Assembly members looking for a bigger stage. Other hopefuls included activists, lawyers and first-time candidates.

Voter turnout in the race was about 9 percent, a low figure that was expected from the moment Mr. de Blasio called a special, nonpartisan election in the middle of winter to fill the seat vacated by Letitia James when she was elected New York State attorney general.

Still, the race to become the city’s public advocate has been an unpredictable, quirky and expensive contest.

By the time polls closed at 9 p.m., the city Board of Elections was looking at spending upward of $15 million to stage an election that was expected to draw one of the lowest voter turnouts in city history. The Campaign Finance Board delivered $7.1 million in matching funds to candidates — twice the amount of the office’s $3.5 million budget, for a position that some people have called to be abolished.

The large number of Democrats in the race was thought to possibly give an advantage to Mr. Ulrich, one of two Republicans in the race, who appeared to finish second on Tuesday.

He was an unabashed supporter of the Amazon deal, is against congestion pricing and is not in favor of closing the Rikers Island jail complex. He criticized Mr. de Blasio more vocally than his fellow candidates, and also obtained the endorsement of the city’s two tabloid newspapers.

Mr. Williams’s win assures him only of being in office for the remainder of the year. Another election will be held in November to fill out the final two years of Ms. James’s term; petitioning for a June primary started on the same day as the special election.

It is unclear if Mr. Williams can consolidate enough support to scare off potential opponents from challenging him in the primary. Bill Lipton, the state director of the Working Families Party, whose endorsement of Mr. Williams provided an important boost, said Mr. Williams had.

“The progressive movement is stronger than ever,” Mr. Lipton said. “This is a decisive victory.”

Correction: Feb. 27, 2019

An earlier version of this article misstated the line of succession to the mayor. The public advocate is first in line to succeed the mayor, not second.