Care clash: Legislation could force nursing homes to add caregivers … but they say they can’t fill positions open now

June 7, 2018

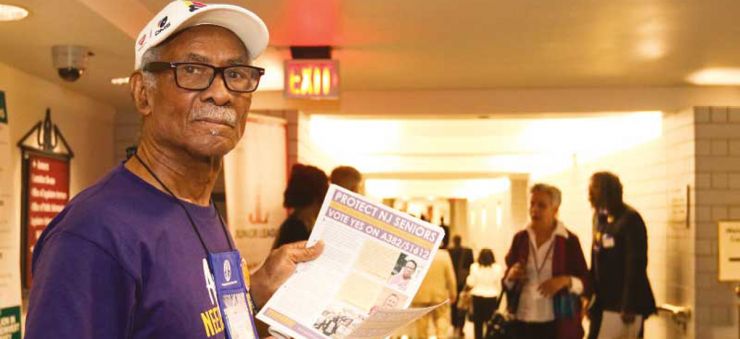

Charles Gordon, a retired nurse aide, traveled to the State House in Trenton with the 1199SEIU union to advocate for the bill covering nursing home workers.

Photo by Alexandra Pais

by Brett Johnson, roi-nj.com

Certified nursing assistants that bathe, dress and do much more for residents at New Jersey nursing homes woke up to new prospects under Gov. Phil Murphy.

That’s because a union that represents them saw an opening for once-vetoed legislation that would mandate the increase of staffing levels of these nonmedical caregivers. Now, it’s quickly moving ahead, much to the dismay of opponents that see it as being a tipping point for a problem-plagued business sector.

Under the proposed law, nursing homes would have staffing ratios to meet: Facilities would be limited to having one certified nursing assistant on staff for every eight residents on a morning shift, no more than 10 per aide in the afternoon and no more than 16 per aide overnight.

An identical bill cleared the state Legislature two years ago but was vetoed by former Gov. Chris Christie. The initiative was pushed for by 1199SEIU, a union that represents about 8,000 nursing home workers in the state.

Bryn Lloyd-Bollard, communications director for the union, sounds confident about the bill’s chances this time around.

“With the election of Murphy, the time was right to focus on this issue again,” he said. “Two years down the line, the issue has only become more urgent. Our members campaigned hard for Gov. Murphy. We expect he’ll sign this into law when it comes to his desk. We’re just working to get the votes.”

Lloyd-Bollard said this legislation would send a message to nursing home operators “that they need to staff adequately in their facilities,” given that the Garden State ranks among the bottom in the nation for average nursing aide staffing-hours per patient.

“And we feel like this is the most clear, straightforward way to manage staffing requirements, because it empowers both residents and their family members to understand how the daily staffing levels at a given facility compare to the standard,” he added.

Several states have passed similar staffing ratio laws. New Jersey’s iteration of the legislation, after it received an approval from the Assembly Health Committee, is expected to be voted on by the state Senate early this month. Lawmakers have heard testimony from union members as well as the bill’s critics.

One of its opponents is Jonathan Dolan, CEO and president of the Health Care Association of New Jersey, a 300-member organization that represents almost half of the licensed skilled nursing facilities in the state and 70 percent of assisted living facilities.

“We’ve been respectful, but also adamant about some of the things we think should happen first in order to promote good health care policy,” he said. “We think it’s looking at one side of a multifaceted problem.”

Dolan said that’s made evident by the fact that the legislation doesn’t take into consideration the direct care sometimes provided by other nursing home staff, such as registered nurses.

Aside from that, Dolan’s association has appealed to legislators to take note of a worsening shortfall of qualified front-line caregivers in New Jersey.

“It’s so bad that some nursing facilities have had job ads for their entire existence,” he said. “I know of a member facility that has had an ad for like 40 years and still hasn’t taken it down.”

There are around 1,800 unfilled positions for certified nursing assistants in the state, Dolan said. He added that an initial New Jersey Hospital Association analysis indicates staffing ratios could exacerbate this by increasing the need for these workers — bringing the shortage up to 3,000.

“But these are positions that there are actually no licensed individuals in the state to fill, and there’s no way to get around that fact,” he said. “Over something like Memorial Day weekend, with everyone on break, you can bet there (was) a lot of senior nurses clothing, bathing and toileting a lot of senior citizens. And it’s unfortunate that this could get worse because of a fast-tracked legislation.”

Rather than being outright against addressing the issue of short-staffing, Dolan advocates for putting the brakes on current legislation while the state makes an effort to increase the available workforce. He’s imploring policymakers to consider funding scholarships and helping to drive recruitment of these workers across the state in partnership with colleges such as Rutgers University.

“Otherwise, we just don’t have the people to meet (the proposed ratios),” he said. “I certainly don’t fault a labor union for working for its constituency, that’s what I’m doing myself. But I just think the timeline is unfair. It doesn’t lend itself to smart, deliberate health care policy.”

Lloyd-Bollard has his own concerns about the workforce. He said there’s a constantly revolving door — with turnover rates nearing 100 percent — at nursing facilities today. And many caregivers are apparently looking for work outside the health care industry altogether.

Claire Wombough, a certified nursing assistant in Manchester Township and union member who has testified in front of New Jersey policymakers, has experienced firsthand what Lloyd-Bollard described.

“I’ve seen many people leave for less stressful jobs,” Wombough said. “You can go work at a place like Home Depot, make only a little less but deal with much less pain on your body.”

It’s not just the job’s veterans leaving, she said, it’s just as often young newcomers to the profession who decide the workload is too much. Wombough believes the staffing situation is rough on both the aides and the residents they care for.

“It’s hard on everyone,” she said. “So, I’m hoping that (the legislation) will not only make things better for us, but for the residents as well.”

Jeanitha Louigene, another union member and certified nursing assistant of 27 years, is certain it’s having an effect on the quality of care provided by nursing facilities.

“I really feel sorry for the residents,” she said. “With the amount of residents we have at once, we really don’t have time for them — they may want to talk, but we can’t do that. We have one person taking care of sometimes 15 or more residents, who are needing the bathroom, water or are in pain. We have multiple people calling for us. But we can only be in one place at one time.”

The union and its members see themselves as being in a crisis moment of caregivers being stretched so thin that it’s putting nursing home residents in jeopardy.

Those against staffing ratios have identified a crisis, too. It’s in the way costs are being driven up for facility operators despite the state being one of the worst in the country in terms of public funding dedicated to nursing facilities, which are required to have almost half its residents be Medicaid patients.

Dolan and other staffing ratio opponents argue the increased pressure on nursing home financials will threaten the future of these facilities amid the so-called “silver tsunami,” the encroaching wave of aging baby boomers in need of long-term care.

“And it’ll become a nationwide story if this becomes the mess that it looks like it’s going to be,” Dolan said.

Once the debate surrounding staffing ratios is ultimately settled in Trenton, the caregivers’ union intends to focus on improving the wages of its members across the state.

“Despite how difficult it is, it’s a very low paying job — with many (nursing assistants) only making $12 or $13 per hour,” Lloyd-Bollard said. “It’s not right that caregivers have to do two or three jobs to make ends meet. These are the people responsible for caring for our state’s most vulnerable people; we should support them.”