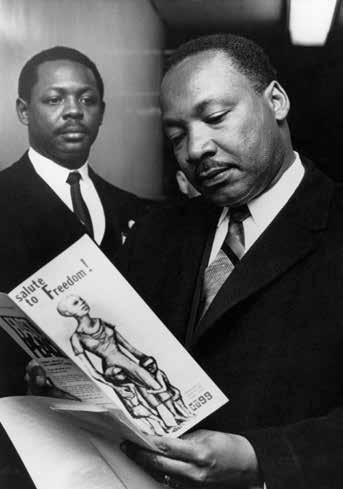

1199 Helped Launch First Poor People’s Campaign

June 24, 2022

The 1969 Charleston strike was a key milestone.

The highlight of the campaign, Dr. King stated, would be a huge gathering that summer of the poor in Washington DC.

Within weeks of making that speech, Dr. King was gunned down while helping low-paid Memphis sanitation workers in their fight for fair wages, better conditions and union recognition.

Just two months later, some 600 members of 1199 attended the Washington Poor People’s March from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial.

The following October, 1199 announced the formation of the National Organizing Committee of Hospital and Nursing Home Employees, with Coretta Scott King as its honorary chairperson.

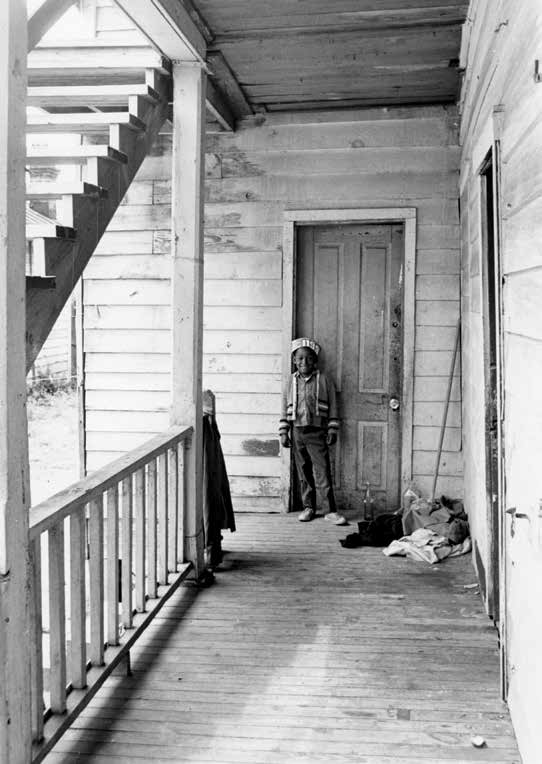

Some months later in 1969, the Union helped to write another important chapter in the Poor People’s Campaign when it came to the assistance of some 450 workers at two Charleston, South Carolina hospitals. The workers had struck to win the reinstatement of 12 unjustly fired workers and to win union recognition.

The strikers, all African American and 90 percent women, worked at the Medical College Hospital of the University of South Carolina (MCH) and at the smaller Charleston County Hospital. They were led by Mary Moultrie, an MCH nurse’s aide whose LPN certification was not recognized primarily because of her race.

The racism and sexism suffered by the workers was typical of subordination in the town. In 1969, MCH had no Black physicians or nursing school students, yet virtually all low paid staffers were Black. Many hospital workers earned just $1.30 an hour. The 1970 census found that 40 percent of Black Charleston families lived below the poverty level.

Although 32 percent of South Carolinians were African American, not one Black state legislator had been elected since Reconstruction. Less than 60 percent of eligible Black voters were registered to vote.

By the third week of April, Charleston had become the scene of mass meetings, daily marches, multiple evening rallies in churches and union halls, and boycotts of stores and schools. More than 1,000 Union supporters were arrested.

The highlight of the campaign was a Mother’s Day march of 10,000 Charlestonians, along with major national leaders like Walter Reuther, president of the United Autoworkers, and Coretta Scott King. Hundreds of New York 1199ers took part.

Afraid that the battle might spread, the Nixon administration pressured MCH to rehire the 12 fired workers and other strikers, and to establish a grievance procedure and a credit union.

Although the agreement did not include Union recognition, Charleston would no longer be the same. In the strike’s aftermath, voting registration skyrocketed, voters elected its first two African American legislators in decades. And Black representation on the City Council jumped from one to six in the subsequent 10 years.

“We won this strike because of a wonderful marriage—the marriage of SCLC and Local 1199,” said Andrew Young, an SCLC leader at the time, and a future UN ambassador and Atlanta mayor.

With the campaign, 1199 had solidified its image as a civil-rights Union. 1199 soon established a beachhead in Baltimore and went on to organize some 7,000 Maryland workers and thousands more in major cities.

The tradition of standing up for economic and racial justice lives on to this day. In recent years, 1199’s leaders, members and retirees have worked closely with Bishop William J. Barber, both nationally and in his home state of North Carolina, most notably in the Poor People’s Campaign led by Bishop. Barber and Rev. Liz Theoharis.

Members have been mobilizing for months for the June 18th Mass Poor People’s & Low- Wage Workers’ Assembly & Moral March on Washington D.C. As the 1199 Magazine went to press, hundreds of members had signed up for Union busses, to make sure their voices would again be heard in the nation’s capital.

1199 Magazine: May / June 2022